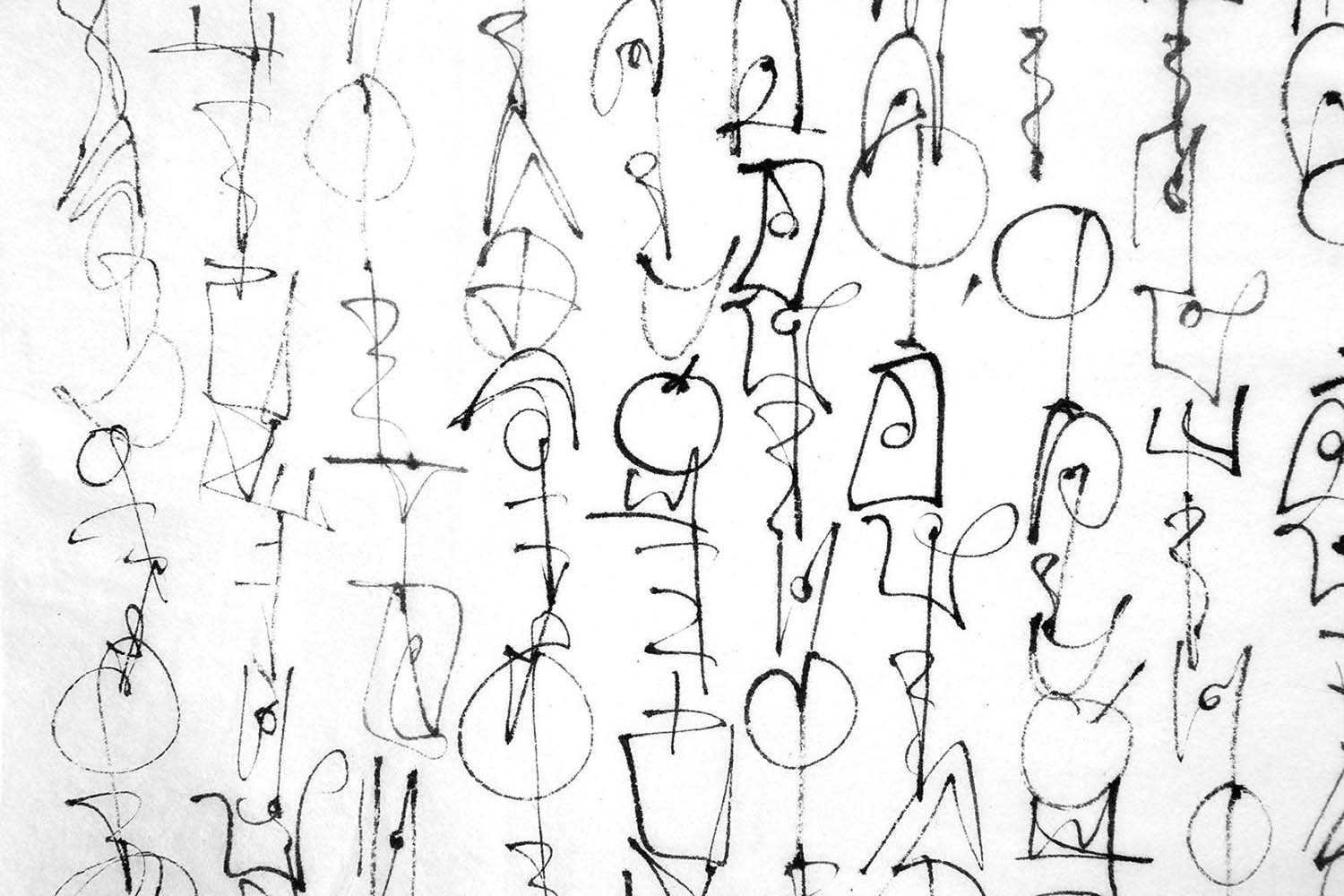

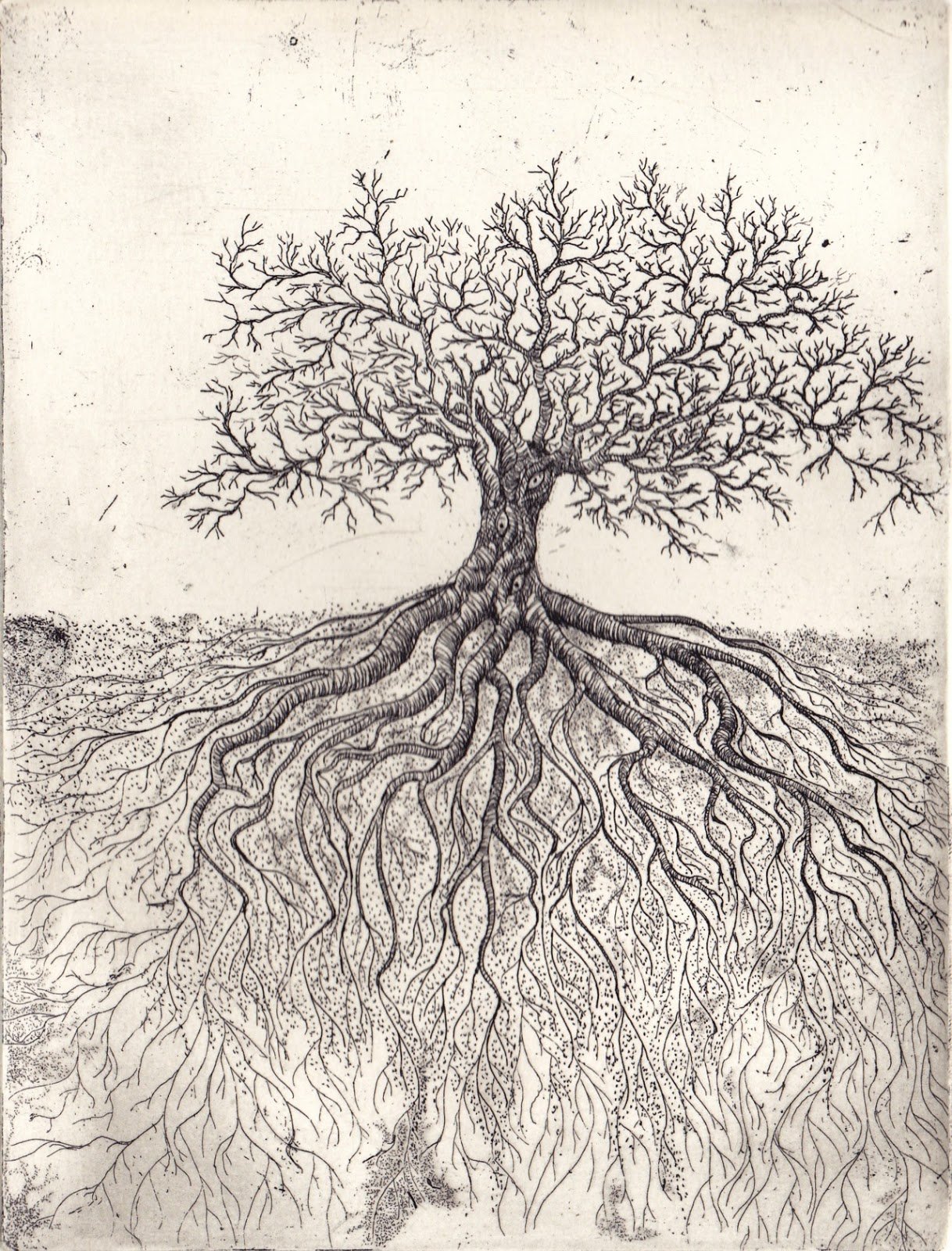

My paintings are landscapes to enter and explore, to unravel. Each a challenge to the viewer to decode the meanings behind the combinations of words, symbols and colors. They are invitations to investigate the significance of the associations between what at first might seem random juxtaposed elements and phrases. Each piece is a dream—a memorandum from my subconscious. I collect materials, gathered by myself and others: a news clipping from the Moon Landing my grandmother saved, a flyer from a concert in Toronto, a ticket stub from a movie, the drawing I made on solstice in the rain. I seek the quality of ‘time’ in these materials; newspapers and books from the early 1900s, discolored with age, an odd, ever-growing collection of timeworn, discarded printed paper scraps. I layer these materials like the rings of trees (compressed time) using a ‘collage painting’ technique I have refined using acrylic paint and a variety of stains, glazes, dirt, ash on wood panels and parts of weathered barns and houses.

“It may be that when we no longer know what to do, we have come to our real work and when we no longer know which way to go, we have begun our real journey.

The mind that is not baffled is not employed. The impeded stream is the one that sings.”

“Who am I?

If this once I were to rely on a proverb, then perhaps everything would amount to knowing whom I haunt.”

The contemplation of the representation of time through layers of organized, categorized, mathematically oriented collaged elements, the struggle to express my most inner thoughts and ideas, the material itself motivates me. This pursuit has awakened in me a vision of eternity. I present my work to you as a documentation of my attempts to express this eternity in myself, my attitude, my joys, my appreciations, my relationship to the past, others—in time. my purpose

“We must start by agreeing that the function of visual art is to convey an infinite number and variety of human thoughts through an infinite number and variety of images. Image must pass thru the artistic conciseness before articulated—understood. Where does image come from? Unconditional expression. A declaration that does not come from others or self. It manifests out of nowhere—emptiness: mushrooms in a meadow, thunderstorms, rust.Not knowing exactly what he is doing, guided by intuition, the artist confronts something not understood, in order to make it more understandable. Contending with this, in fact possessed by it, he prospects the imagistic frontier, far out into the unknown, bringing back a piece, and transforming that piece into mythological image. We gaze at art ignorantly and become informed by it, but we struggle to say exactly what we see. It is the unknown, shining through, in partially articulated form. When the unknown in a work of art resonates with the unknown inside the viewer, that I believe is the purpose of art. ”

About Me

-

2023 Beeple Studios , Charleston, SC

2023 Manifest Gallery , Cincinnati, OH

2020 ThunderSky INC, Cincinnati, OH

2019 934 Gallery, Columbus, OH

2018 Secret Artworks, Cincinnati, OH

2014 Greenwich House Gallery, Cincinnati, OH

2012 Synthetica-M, Cincinnati, OH

2011 BoxHeart Gallery, Pittsburg, PA

2009 Chapman Friedman Gallery, Louisville, KY

2008 El Ojito Springs, Tucson, AZ

2008 Art Access, Columbus, OH

2007 The Marx Gallery, Covington, KY

2006 The Kirsten Bowen Gallery, Columbus, OH

2005 The Schumacher Gallery, Columbus, OH

2004 St. Mary’s Cathedral Basilica, Covington, KY

2003 Cox Fine Arts Center/OSF, Columbus, OH

2002 Edward Hopper House, Nyack, NY

-

Kroger West Chester, Ohio, Commission

Hotel Covington, Collection

“Love and Other Drugs”, Edward Zwick Film

Nancy “Nana” Lampton, Collection

Extreme Makeover Home Edition, Television Series

Tracie McGarity Interiors, Commission

EMH&T, Collection

Fresh A.I.R Gallery, Collection

Excellent Pictures & Words, Commission

Ottos Restaurant, Collection

Ivonne Lie, Indonesia, Collection

-

I paint my pieces on wood panels, old pieces of barn siding and houses, cloth is not rigid enough to hold up to the collage. The work is mixed-media collage, compromising multiple layers using wallpaper paste, contact cement, spray adhesives, along with alternating layers of water based and oil-based mediums: acrylics, watercolor, ink, oil and charcoal. I use urethanes, varnishes and shellacs to stabilize extremely thick applications of wax, plaster, ash, dirt, sawdust, occasionally including fabric, snakeskin, rose petals, leaves and other found objects. Photographing, cataloging steps and processes—results, combining and reworking pieces digitally, in my most recent works—implementing Ai processes and filters. Moving back and forth between physical and digital, dancing with creation, embracing the “mistake”. I am trying to arrange collaged elements with a variety of media until those elements do not seem arranged, until they are as natural as water flowing, the wind in the trees. Not forcing intent on the viewer, letting the viewer find the unknown in the painting for themselves, not propaganda but TAO.

I believe that a newspaper headline from 1965 holds the energy of that event, that mass consumed printed materials contain residues, hive-mind; scraps cut from other drawings are markers of time and energy—revenants. That they imprint some sort of psychic residue on the viewer; those materials used become the ghost of that use. The effects of colors, cutting up old books and newspapers, and digital printouts an authentic journey into my subconscious - the infinite possibilities of existence. I work solely with ghosts, weaving them together in a way that allows the viewer to tell the story—to dream, gazing at the landscape. The viewer’s personal experience dictates the emotional value of the elements; a movie ticket, for instance—an action film, but the memory is of the last time you held your love’s hand.

In my studio, I have a large rolling cabinet filled with all my collage materials. This cabinet is a physical representation of my subconscious, a dream box. There is no organization, everything thrown in like a trash can. I have spent countless hours digging through these scraps and pieces. These pieces have touched me deeply, personally. I can remember working on old paintings just by seeing a scrap or remnant from the cabinet. I have been collecting these scraps for nearly twenty-five years. Every piece of work I have ever created started as scraps from this box. The box itself has evolved over the years, beginning as a collection of tubs. Old newspapers and magazines bought at thrift stores and eBay auctions, old drawings and paintings, scraps given to me by friends, family and followers of my work. Each element of the painting exists in an assigned moment in time, using numerical principles such as phi and logistics maps and studying Vedic math and sacred geometry—Thangka Paintings—to pair textures and colors, balance the composition, giving the work a symbolic or sacred dimension, a dream scene, a riddle. The paintings are landscapes to enter and explore onto which the viewer can project subconscious meanings, triggered by the revenants. My process involves working an area until it makes sense and then disrupting in with a brush stroke or gluing in a scrap of something; a constant circular process of build and destroy. This process mimics time, the effects of age, the seasons–life on the farm—this earthy aspect has bloomed over time into vast complicated language. Subtraction is also crucial. Carving is used to remove materials from the painting's surface, painting through subtraction. Creating spontaneously, aggressively the surface sometimes marred, gouged and sanded, destruction is as an important element as creation—never be afraid to make mistakes or ‘ruin’ a painting. This painting process mimics meditation by not allowing an image to become seated in the mind and subsequently forced on the viewer. I also use stencils and screen printing, screening through drapes, which create an ‘imperfect’ print, arbitrary mistakes in patterns representing the chaotic nature of everything.

While working, I stop, walk away and look—trying to “truly” see what is being created and I photograph everything. Documenting processes and materials, building vast digital libraries of paintings and stages. My most recent work is digital, using an iPad and Pencil, implementing the same collaging techniques using the entirety of my catalog as source material.

-

I was born in a small farming community where the North Fork and South Fork of the Licking River merge in Northern Kentucky. My parents came from farming families, and we farmed tobacco and cattle. The Licking River runs north, and I have heard that there are only seven rivers that run north. I doubt that is true, but I do know that the town of Falmouth gets wiped out by floods nearly every 33 years. My parents worked jobs, and we farmed, when I was young my mother would take me to the neighbor’s house Ellen Jones her husband Al drove a truck for Sears, she would give me her son’s old comic books and a pad of typewriter paper, and I would trace the covers. It was a challenge for a boy too young to write and I would frequently lose my temper. In that process, I found my own way to hold a pencil. My Grandmother Rosemond Mann, a retired schoolteacher, said to leave me alone. I was good at drawing and didn’t want to disrupt that by holding the pencil correctly. Grandma let me experiment with papier mâché, I made dinosaurs and space shuttles complete with solid rocket boosters and external tank. On snow days at my Grandma (Alta Mae and her twin sister Alma Fae Fryer) Johnston’s house, she lived in an old rock house, the Fryer House, across from the elementary school (now a museum and office of the historical society) we would walk to the Farmer’s Market, and I would ask Keith Fardo if he had any cardboard boxes. I would spend the day making boats, planes, trucks out of the boxes, cutting the shapes and using masking tape.

I was always drawing, checking out drawing books, and origami books from the library memorizing the pages. In 7th grade, I met Brenda McGinnis, the art teacher. She thought I was talented and helped nurture my skills. In fact, she gave me the only formal fine arts training I have ever received to this day. When I went to high school, she followed and was my art teacher for four years and helped me get into college, a graphic design trade school, ACA College of Design in Cincinnati.

In 1996 a received an associate degree in Graphic Design from ACA and was working as a Graphic Designer for a retail design firm in northern Kentucky. Worked a couple of different design jobs and lived in the Caribbean for while working for an advertising firm and ended up in Columbus, Ohio, working for another Retail Design Firm. The design work wasn’t creative enough for me and eventually I came to an impasse with my boss in Columbus and found myself drawing unemployment in 1999.

There I was twenty-three, living in a small apartment in an enormous complex with a roommate who had graduated from CCAD with an Industrial Design Degree. He had some art supplies, and I had nothing but free time, so one night I started painting. In a lot of ways, it was the first “serious” painting I had ever created. The only purpose was to show my roommate I was an artist. That painting ‘Trouble for the Voinovich Boys’ was very successful not only did it convince my roommate I “was” an artist, but it later was the first painting I ever shown in a gallery, The Edward Hopper House in Upper Nyack New York.

In 2005, my Grandfather Virgil Mann passed away and some of his property auctioned and I purchased a couple of acres containing the old garage, barn and corn crib. I lived in Columbus and would load up my van with all my materials and drive down to paint in and around the barn. I used whatever I could find to paint on and created 100s of pieces over the next 2-3 years. In 2007, I moved into the old farmhouse and became a farmer, turning one of the upstairs bedrooms into a studio. The farm sold in 2017. Theartofmann studio on Crystal Lake came into being and is where I currently work…

“Thought-provoking pieces …powerful, intriguing, and pleasing to look at.”

ARTISAGHOST

“Mann is one of the artistic visionaries of my generation. His worldview is conflicted in a self-effacing way; he is aware of our troubles, and wishes to do more than observe, but isn’t necessarily idealistic enough to commit to the causes of the Twitter people…so he draws up fences around what is his, and looks outward, a documentarian who spurns the newsfeed in favor of old news clippings, using the shapes of found scraps of linoleum and elderly farming implements to describe a rusted America: a culture of fertile rot, hopeful in its decay, optimistic in entropy.”

“Mann’s work is perfectly balanced between quiet and chaos, like a traveler’s letter, a mosaic of emotions on a wide and empty colored landscape.”

Phi: The Golden Ratio = 1.61803399

The golden ratio has been claimed to have held a special fascination for at least 2,400 years.

According to Mario Livio:

Some of the greatest mathematical minds of all ages, from Pythagoras and Euclid in ancient Greece, through the medieval Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa and the Renaissance astronomer Johannes Kepler, to present-day scientific figures such as Oxford physicist Roger Penrose, have spent endless hours over this simple ratio and its properties. But the fascination with the Golden Ratio is not confined just to mathematicians. Biologists, artists, musicians, historians, architects, psychologists, and even mystics have pondered and debated the basis of its ubiquity and appeal. In fact, it is probably fair to say that the Golden Ratio has inspired thinkers of all disciplines like no other number in the history of mathematics

“… Avalokiteśvara vowing never to rest until he had freed all sentient beings from saṃsāra. Despite strenuous effort, he realizes that still many unhappy beings were yet to be saved. After struggling to comprehend the needs of so many, his head splits into eleven pieces. Amitābha, seeing his plight, gives him eleven heads with which to hear the cries of the suffering. Upon hearing these cries and comprehending them, Avalokiteśvara attempts to reach out to all those who needed aid, but found that his two arms shattered into pieces. Once more, Amitābha comes to his aid and invests him with a thousand arms with which to aid the suffering multitudes.”

“Men do not live once only and then depart hence forever. They live many times in many places, although not always on this world. Between each life there is a veil of darkness. The door will open at last and show us all the chambers through which our feet have wandered from the beginning…”